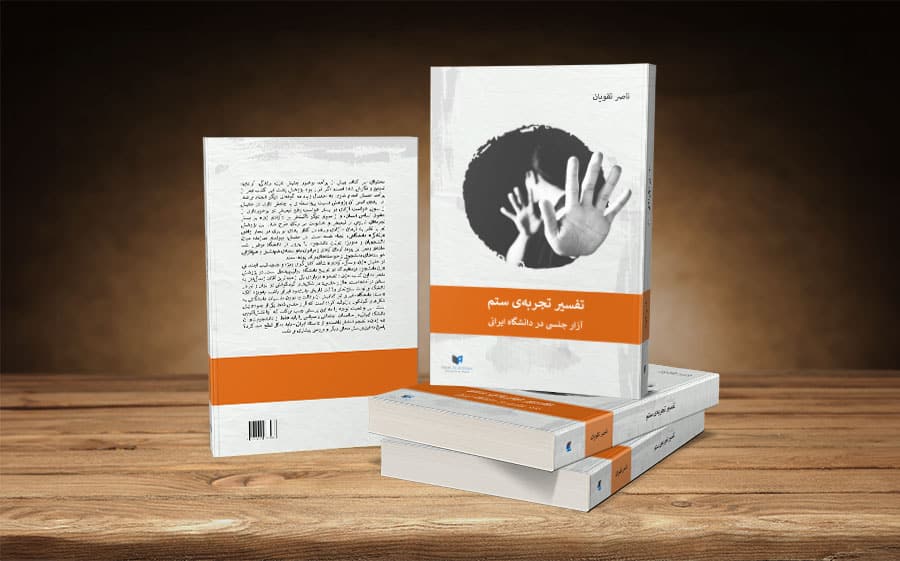

The content of this book was compiled and written before the fervent rise of the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement. That event shook every aspect of Iranian life like an earthquake, making it a true turning point in the contemporary history of transformations in Iran. Many things changed, from values and perspectives to friendships and collaborations. The impact of these changes extended to academia, altering academic teaching and research priorities. If the research behind this book had been conducted after the movement’s emergence, it would likely have been approached differently. Nevertheless, the core concept of the research remains directly connected to the movement. On one hand, the movement called for freedom based on the desire to eliminate all forms of discrimination in accessing fundamental human rights. On the other hand, its emphasis on “women’s freedom” was rooted in a historical experience of discrimination and violence against women. This research was also conducted with the aim of achieving “women’s freedom,” alongside the idea of equality within the real context of academic “life.” In the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, a constructive connection was established between students, particularly “female students,” and the broader society. The link connecting these groups was the shared aspiration for freedom and equality, achieved through the convergence and synergy of student and women’s demands. In the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement, we witnessed the unprecedented activism of the “female student,” a social type unparalleled in the history of Iranian universities.

In the research that led to this book, the “female student” has spoken out about one of the most significant afflictions of her life and asserted her voice. “Sexual harassment,” in its various forms in Iran and at universities, can exemplify the historical depravity of the Iranian patriarch/man. The Iranian “university professor” has also, to some extent, reproduced this depravity in academic relationships in various forms, with sexual harassment being just one manifestation. This reality draws attention to whether the role of the Iranian university in social and political relations should be expected only from students, particularly female students, and whether we should entirely lose hope in the “Iranian professor.” Answering this question, however, requires another opportunity and further investigation.