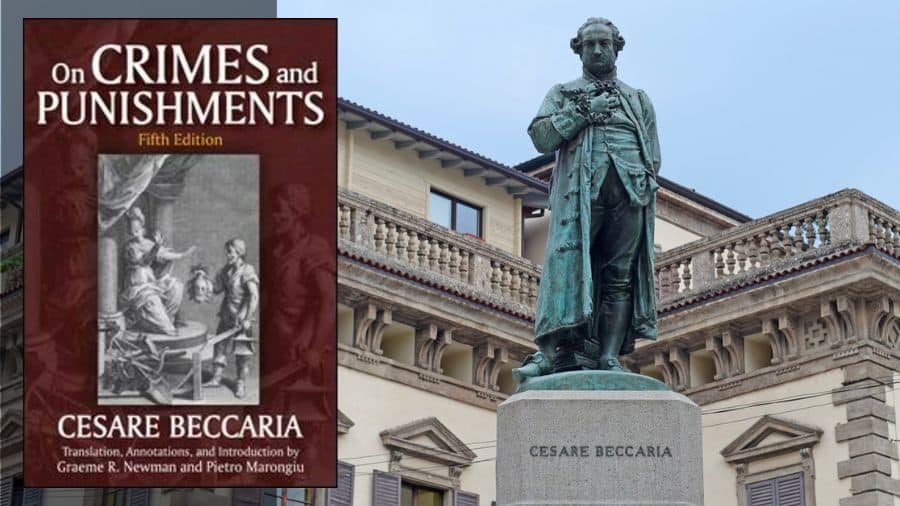

Marchese Beccaria Cesare Bonesana published the book “On Crimes and Punishments” [i] in 1764. One of the most famous paragraphs of the book in the history of Penology is his criticism of “torture” and the “death penalty”. Beccaria’s book is considered one of the most important turning points in the intellectual flow of Milan, since it is an attempt for fundamental reforms in criminal and legal justice. Even today, after more than 250 years, the issues of torture and execution remain sensitive. Even though all kinds of torture are rejected in international forums today, we know that governments in all parts of the world torture citizens under various pretexts. Regarding the death penalty (capital punishment), there is not even a theoretical agreement on paper, and many countries have included a place for the legal murder of citizens (or sometimes non-citizens) in their criminal laws. Therefore, the questions of Beccaria’s text can be considered still open [ii].

Beccaria mentions at the beginning of the sixteenth chapter of his book titled “On Torture” that at that time many governments force a person who is only suspected of committing a crime to confess under interrogation, to reveal his contradictions, or even to confess to doing things he did not do. He argues that torture is an act outside the principle of justice and based on the “right of force” and therefore has no legal legitimacy. The problem with torture is that it claims to apply part of the punishment before the crime is proven [iii]. In fact, since the fundamental principle of law is based on the secular assumption that all human beings are innocent in the beginning (unless proven otherwise), then we have no justification to punish a sinner before proving the crime [iv].

In the case of the death penalty, the issue is more complicated. In fact, in the philosophical discussions of criminology, there are different positions to discuss the existence of “punishment” or “punishment”; from utilitarian reasons (such as Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill) to criminal reasons (such as Kant) or various intermediate positions. Meanwhile, the issue of the “death penalty” is the most difficult. We can define the death penalty as “the intentional killing of a hypothetical or real offender for his offense”. Historically, the death penalty has been considered the most common punishment for suicide [v]. The reasons utilitarians favor the death penalty are that it can be a deterrent for potential murderers because for the overwhelming majority of people, the fear of death is the greatest fear [vi]. Kantians and criminologists argue that when someone murders an innocent person, in fact, in this act, he has already considered himself worthy of death [vii].

In Chapter 28 of his book titled “Death Punishment”, Cesare Beccaria presents several arguments against the death penalty. The most important argument relies on the principles of secular laws. If the laws derive their legitimacy from the people and since someone who has not lost his mind cannot give up his “right to life” [viii], then “the death penalty is not a right, but a declaration of war by a part of society against a citizen is” [ix].

Of course, we should note that Beccaria lists exceptions for the “death penalty”. For example, when the government is in danger or at war, this punishment is permissible. Because in a crisis situation (if the issue is not just an excuse or false claim of crisis) the right to life of the citizen is placed in front of the right to life of other citizens. In fact, this argument becomes weak from this point because this loophole can later be used as an excuse for governments. This condition also prevails in a war situation; This is why in wars, people are called by the government to participate in the war and thus suspend their “right to life”. For example, we know that during the French Revolution, a huge movement was launched to abolish torture and the death penalty. Torture was abolished by referring to models such as Beccaria’s reasons. However, although the death penalty for public crimes was abolished, due to the critical situation after the revolution, the death penalty for “treason against the country and the revolution” remained. The plan that the revolutionaries thought was that the person who was sentenced to death should not be tortured (tout condamné à mort aura la tête tranchée) and the result was a famous invention called the “Guillotine”. This device, which today is a symbol of terror, was actually intended to minimize unnecessary pain. Although the guillotine was finally used in France in September 1977 and the death penalty was completely abolished in France, the philosophical issues surrounding “execution” are still open and are considered to be current issues in most parts of the world.

References

Cesare Beccaria, Mar, Cesare marchese di Beccaria, and Cesare Beccaria. Beccaria:’On Crimes and Punishments’ and Other Writings. Cambridge University Press, 1995.

Goldstein, Warren (2006). Defending the human spirit: Jewish law’s vision for a moral society. Feldheim Publishers. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-58330-732-8. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

Kant, Immanuel. “Justice and Punishment (Continued).” Philosophical Perspectives on Punishment, n.d., 102.

Mill, John Stuart, and Jeremy Bentham. Utilitarianism and Other Essays. Penguin UK, 1987.

Murtagh Kevin, “ Punishment,” The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ISSN 2161-0002, https://iep.utm.edu/, 9/22/2021.

Index

[i] Dei delitti e delle pene in Italian. In English, this book is translated as “On Crimes and Punishments,” which is similar to the title of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s book, “Crime and Punishments”.

[ii] It is interesting that centuries before Beccaria, Ibn Maimon (Jewish philosopher of the 12th century) raised points against the death penalty and claimed that the social effect of freeing 1,000 sinners is better than the damage that the execution of one person has on the society’s behavior. However, Beccaria’s argument is philosophically powerful.

Goldstein, Warren (2006). Defending the human spirit: Jewish law’s vision for a moral society. Feldheim Publishers. p. 269. ISBN 978-1-58330-732-8. Retrieved 22 October 2010.

[iii] In some religious approaches in Christianity (and in other religions) it was said that if it turns out after torture that a person was actually innocent in the matter in question, from the divine point of view of his general sins (since mankind has always been guilty since the age of Adam) is reduced or his torture is considered as a reward in the hereafter. Many religious authorities used to kill with the same argument that if the victim is innocent, he will go to heaven, and if he is guilty, justice has been done.

[iv] Mar Cesare Beccaria, Cesare marchese di Beccaria, and Cesare Beccaria, Beccaria:’On Crimes and Punishments’ and Other Writings (Cambridge University Press, 1995), 39.

[v] “ Punishment,” by Kevin Murtagh, The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy, ISSN 2161-0002, https://iep.utm.edu/, 9/22/2021.

[vi] John Stuart Mill and Jeremy Bentham, Utilitarianism and Other Essays (Penguin UK, 1987).

[vii] Immanuel Kant, “Justice and Punishment (Continued),” Philosophical Perspectives on Punishment, n.d., 102.

[viii] This part of the argument based on the assumption of continuity of “right to life” is very similar to Rousseau’s argument with the assumption of continuity of “right to freedom”. However, some people can give reasons, in addition to someone who sacrifices his life in battle and in some way passes the “right to life” in the name of sanity, we also face this challenge in issues like “Utonasia” that in times of peace and security someone wants to give permission to the doctor to take his life.

[ix] Cesare Beccaria, marchese di Beccaria, and Beccaria, Beccaria, 66.